At the end of Evicted, his beautifully written ethnography about poverty and housing in Milwaukee, Mathew Desmond writes: “I have been blessed by countless acts of generosity from the people I met in Milwaukee. Each one reminds me how gracefully they refuse to be reduced to their hardships. Poverty has not prevailed against their deep humanity” (336). Desmond writes with empathy about families that are struggling in America and doing the best they can under harsh circumstances. His empathy is remarkable, for families at the margins – whether by poverty, or other forms of difference, such as drug addiction – are often the object of indifference, pity or contempt. Photographs of families who struggle can create or elicit these kinds of feelings especially when they circulate rapidly, online, in spaces that seem to produce instantaneous vitriolic judgment.

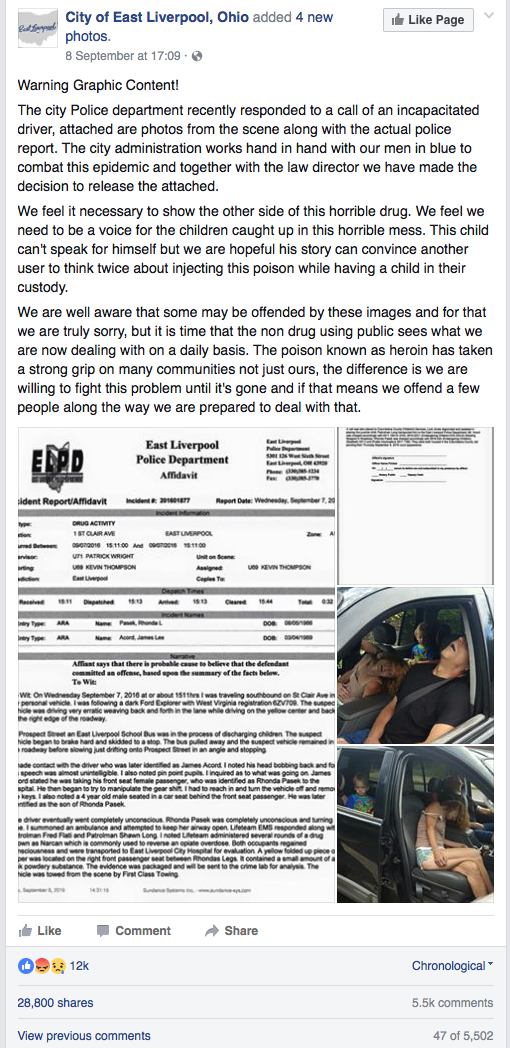

Take, for example, the recent two photographs of two adults overdosing on heroin in the front seat of their car while a small child sits in a car seat behind them. The woman’s face is death-like and gray; her head lolls forward as her body slumps towards the man, her shorts riding up and her shirt falling off. He is similarly posed, although his body is not as exposed. The photographs were taken by police in East Liverpool, Ohio, and, along with an incident report, were posted on the city’s Facebook page under the heading “Warning Graphic Content!” East Liverpool’s Facebook post has been shared 28,800 times, has received more than 5,000 likes, and over 3,500 each of angry and sad emoticons. The city claimed it was necessary to publish these photographs as a deterrent to drug use. Taking part in a long history of photographs of families in crisis used, purportedly, for “social good,” the photographs of the overdosing pair are not unique. While their objective might be to deter, instead they shame, judge, and exacerbate the otherness of those who suffer.

Taken as part of a police investigation, these are crime scene photographs that are to be used as evidence in court. They also happen to capture a moment of deep sadness and despair in one family. The child’s face was blurred once the photograph reached news media, but the initial post shows the faces of these three family members, and the two adults are named. Although first thought to be the child’s mother, the woman in the photograph is now reported to be the child’s grandmother who had recently been awarded custody of him. There are many other family members, not pictured here, who are connected to these traumatic images, for any family photographs operate in a web of connections. What of the child’s parents, who have already lost custody of their son? Or, the other family members who have now taken him in? How does the public act of shaming affect them, or hurt them? And, a 4-year-old boy will be forever attached to the destructive narrative about his family that is constructed through the circulation of the photograph.

Like Alberta and British Columbia, Ohio is the site of an epidemic in heroin use. This epidemic is made worse by the contamination of low-grade heroin with illegally produced fentanyl, a powerful synthetic opiate used in palliative care. It is a particularly deadly combination. We do need to know about the dangers of drugs, addiction, overdose. Sometimes, as in Evicted, the stories of those caught up in a crisis can help to draw attention to it, and that attention could, ostensibly, aid in making positive change. In order for those stories to be powerful, however, we need to be able to connect to them and feel empathy for the people depicted, both in words and in photographs. Desmond’s character of Scott, for example, allows us share and understand the depth of his struggles with fentanyl and heroin. We see him at his lowest moments, when after losing his place in a rundown trailer, he tries to get help with his addiction. In one particularly harrowing scene, a psychiatrist asks him about the sexual abuse he underwent as a child. The doctor asks him how old he was and Scott replies “Young. From four to [...] ten.” He then replies ‘no’ to the doctor’s questions about ever having told anyone and having or wanting treatment for it. Yet, Scott is the only person in Desmond’s book to find a way out of the cycle of poverty and eviction. He does so when he finally tells his mother he lost his nursing license for stealing drugs and asks for her help. But, both he and his family are protected by the pseudonym Desmond has given him. His story is raw, painful and powerful, but he retains his dignity for he is not named.

The ways in which the photographs of the pair in Ohio were taken (as part of a criminal investigation at the moment of near death), circulated (attached to an incident report and under a warning) and re-circulated (sensationalized on countless blogs and in online media with forums that allow hateful comments) preclude empathy and emphasize otherness. They use a family’s private moment of suffering and near death to reinforce ideas about addiction as moral failing and to elicit our collective outrage. And, encouraged by headlines like “HORRORS OF HEROIN Shocking moment drug addict couple pass out after overdosing on heroin with their TODDLER in the back seat of the car,” viewers participate in this outrage willingly, using phrases like “disgusting family,” “[parents] are beyond hope obviously!,” “skag heads as parents” and “two morons” to describe the adults depicted in the photographs. Even staid headlines such as the Globe and Mail’s “Images of allegedly overdosed couple in Ohio with boy in car go viral” draw comments like “that poor child will (& should) be taken away from these two dead beats.”

What purpose does this public shaming through photography serve, other than to further marginalize the family depicted? It contributes to the cause of drug addiction, which is often rooted in unbearable pain, including shame. Opiates are painkillers; this is why they work so well when we are recovering from surgery, or dying from cancer. And, as Gabor Maté has pointed out, “we ‘feel’ physical and emotional pain in the same part of the brain (In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters with Addiction, 155). People who take opiates are trying to alleviate overwhelming pain. East Liverpool’s police photographs depict two people in so much pain that they are willing to court death to find relief. The circulation of the photographs only creates more suffering, more shame for those who take drugs, and more misunderstanding for those who do not suffer the same kind of pain.

Instead of participating in the public shaming of families who are struggling with addictions, we could respond with empathy and ask one simple question: why are you hurting so much? And more broadly, why are so many people in such tremendous pain?

Brian Allen, one of three men responsible for the decision to post the photographs, explains his decision to The Daily Mail: “If we hadn't, Rhonda Pasek would have received a slap on the wrist and that little boy would have gone back to her - that's not going to happen now [..] I doubt she will see that child again.” And therein lies the pain.